How Water-powered Mills Work

Singleton Mills homepage > Different types of mills > How water-powered mills work

Watermills in Creeks compared with Tidal Mills

Watermills and Tidal Mills both used Waterwheels to capture the power of flowing water and drive the mill machinery.

Above: a pair of wooden waterwheels that were used to power an historic watermill in Dunster, UK. Photograph by Anne Dollin, 2012.

Two main types of water-powered flour mills were used in New South Wales during the 1800s: Watermills using water running down a creek or river, and Tidal Mills capturing tidal water flows.

1. Watermills with Millponds in Creeks

A dam could be built across a creek with a reliable water flow. This collected water in a 'Millpond.'

When the Millpond was full, the Sluice Gate in the Millpond wall would be winched open creating an opening at the bottom. The stored water from the Millpond would gush through this opening under pressure. A channel or Millrace may sometimes also be built to carry this fast-flowing water down to the Mill.

At the Mill, the flowing water would push against the paddles or buckets of the Waterwheel, turning the Waterwheel, which in turn powered the machinery inside the Mill.

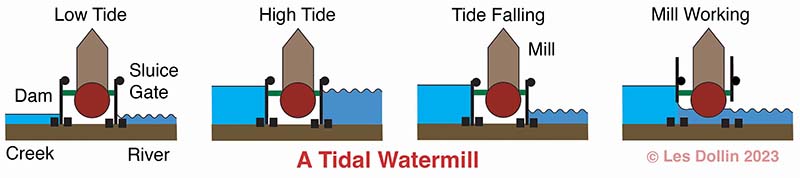

2. Tidal Water Mills

In some rivers in coastal areas, the water levels rise and fall, twice a day, due to the ocean tides. Near these tidal rivers, a dam could be built across a creek mouth, or other low area. Water would enter the dam through one channel in the dam wall, as the tide rose. At high tide, the water in the dam would reach its highest level, then a gate would close this channel.

The Waterwheel of the Mill was mounted in a second channel through the dam wall. After the tide had fallen far enough again, a Sluice Gate in this second channel would be winched open creating an opening at the bottom. The stored water from the dam would gush through this channel under pressure, back into the river.

This fast-flowing water would push against the paddles of the Waterwheel, turning the Waterwheel, which in turn powered the machinery inside the Mill.

Note: The first channel, which allows water from the rising tide to fill the dam, is not shown in these diagrams.

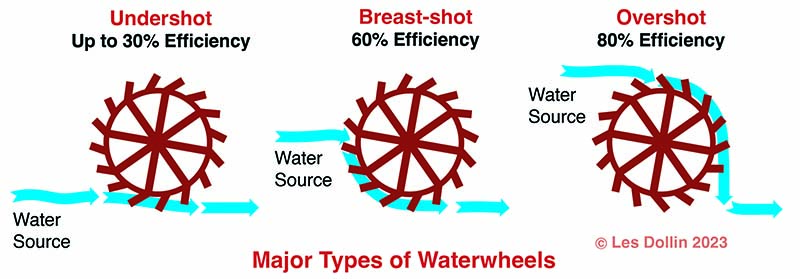

Undershot, Breast-shot, and Overshot Waterwheels

Mills used different designs of waterweels in different situations. The major types were the Undershot, The Breast-Shot and the Overshot waterwheel.

In an Undershot waterwheel, the water stream ran underneath the wheel to power the mill.

In a Breast-shot waterwheel, the water stream was directed at the mid section of the wheel to power the mill.

In an Overshot waterwheel, the water stream was directed onto the top of the wheel to power the mill. This system was favoured because it was the most efficient and it produces the most power.

Source of efficiency ratings: British Hydropower Association.

The Machinery Inside the Mill

Inside the Mill, the waterwheel was connected to the grinding Millstones using massive rotating shafts and a series of huge cogs.

Above: a massive vertical wooden drive shaft and huge wooden cogs inside an historic watermill at Lyme Regis, UK. Photograph by Anne Dollin, 2012.

The grinding Millstones were in pairs and each millstone weighed up to one tonne. Grain (usually wheat, barley or corn) was fed into the pair of Millstones through a hole in the top stone. The bottom Millstone was fixed to the floor, while the other Millstone rotated to grind the grain. Flour was collected and stored in bags.

Millstones

In the earliest years of the New South Wales colony, cheaper gritstone millstones, such as Derbyshire Greys (or Derbyshire Grays) were used in many of our mills. These millstones were cut from a single piece of coarse, hard, quartz-like sandstone, called Millstone Grit, that was quarried in the Peak District of Derbyshire, UK.

| Read about the different kinds of millstones that were used around the world. • French Burr Stones • Basalt-like Cullin Stones • Millstone Grit • Puddingstone • Granite • Limestone • and more! |

Then in a surprising twist to the story in Australia, some unusual millstones were cut from Calcarenite Limestone on Norfolk Island during their First Colonial Settlement (1788–1814), and these were successfully used in the mills of that settlement.

In 2024, we discovered that the two old millstones that are on display at Kurrajong, NSW, are rare examples of Calcarenite Limestone millstones – and they were almost certainly quarried on Norfolk Island!

Above: detail of one of the extremely rare Calcarenite Limestone milllstones from the Singleton watermills at Kurrajong, NSW. Photograph by Anne Dollin, 2023.

| Read the full story of Kurrajong's Calcarenite Limestone Millstones and their link with Norfolk Island. |

Soon, however, demand grew for the white flour that could be produced using expensive French Burr Stones. Newspaper advertisements show that they were in use in at least one Singleton mill at Kurrajong by 1824 and in two Singleton mills at Wisemans Ferry by 1841. French Burr Stones were constructed from segments of quartz stone that were bound together with steel bands. This special stone was mainly quarried near La Ferté-sous-Jouarre in northern France, and could produce particularly good white flour.

Above: A French Burr Stone, proudly displayed by M. Joseph Markey at the Steenmeulen Windmill in France in 2012. Photograph by Les Dollin.

| A close up look at Australia's French Burr Stones ... and a hunt for their 30 million year old fossils! |

Steam-powered Mills

By the 1830s, steam-powered flour mills began to be constructed in regional New South Wales. Millstones were still used initially to grind the grain. However, the power source for the mill, the waterwheel, was replaced by a much more powerful steam engine.

Further Reading

• Types of Mills • How Steam-powered Mills Work • Watermills at Kurrajong • Tidal Mills at Wisemans Ferry • Steam Mills at Singleton •

Read More About Millstones

•• Overview •• French Burr Stones •• Basalt-like Cullin Stones •• Millstone Grit •• Old Red Sandstone, Puddingstone, and Lodswoth Stone •• Granite •• Limestone •• Artificial Millstones •• Norfolk Island Millstones •• Colonial Millstones ••